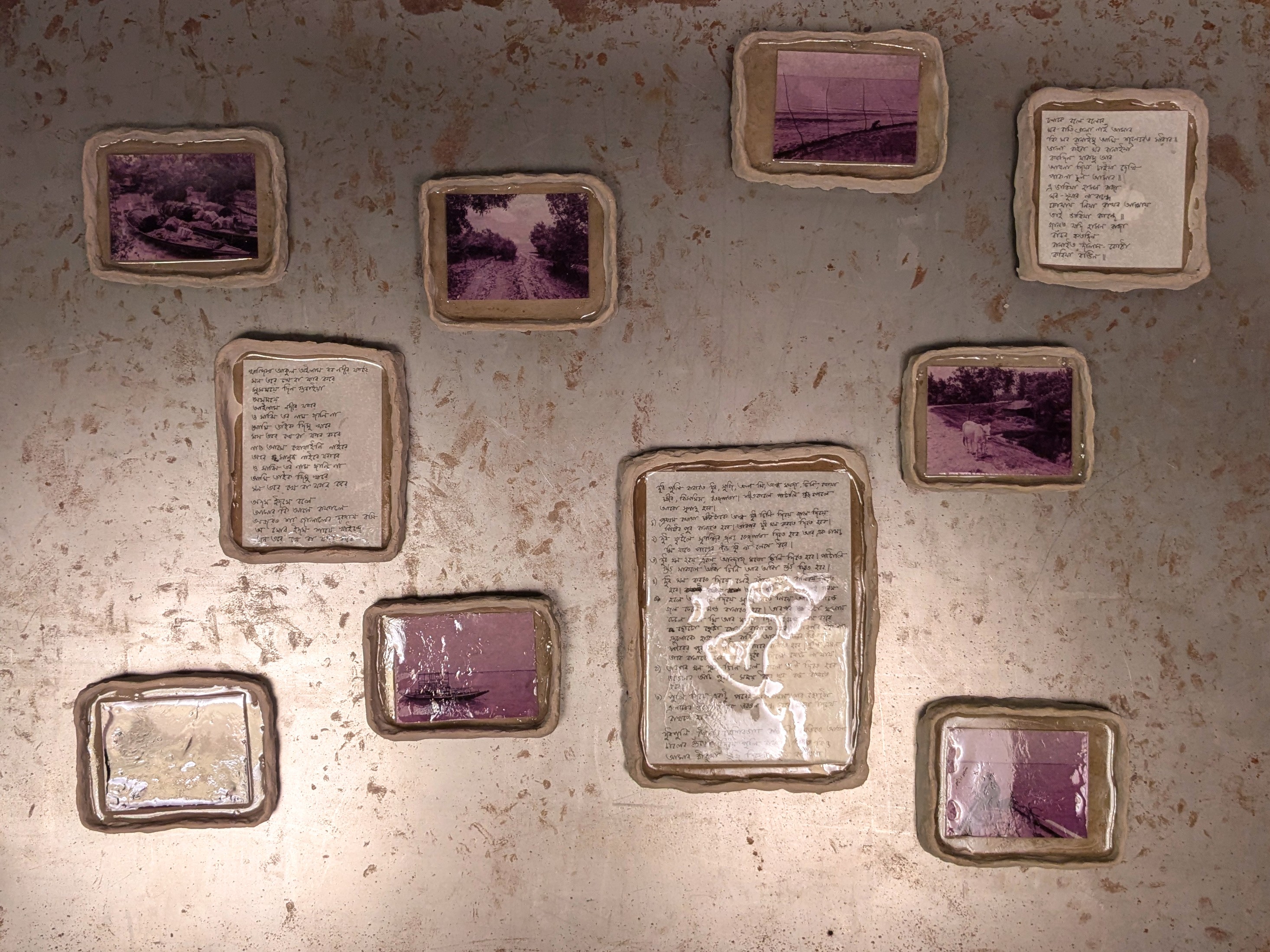

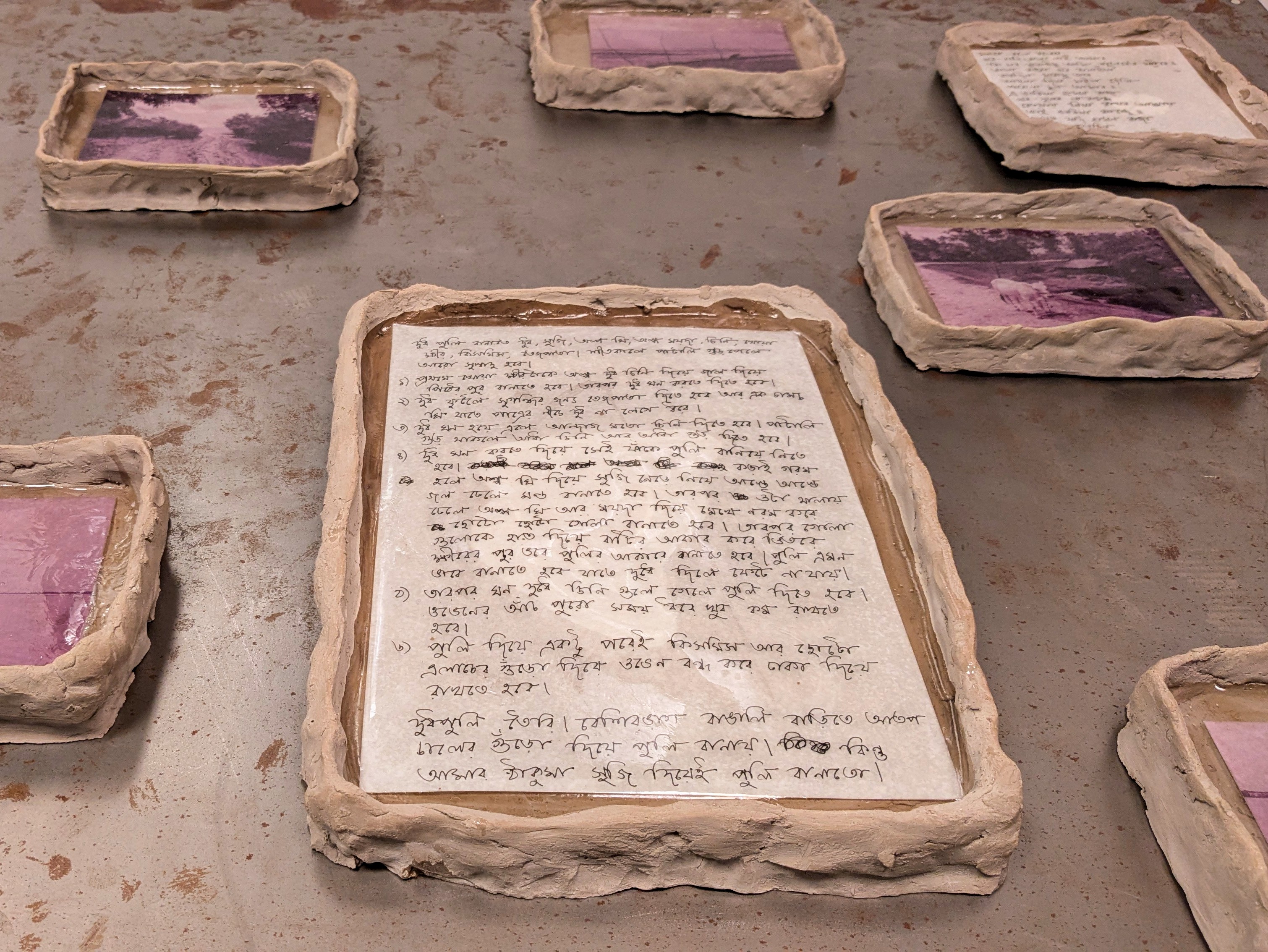

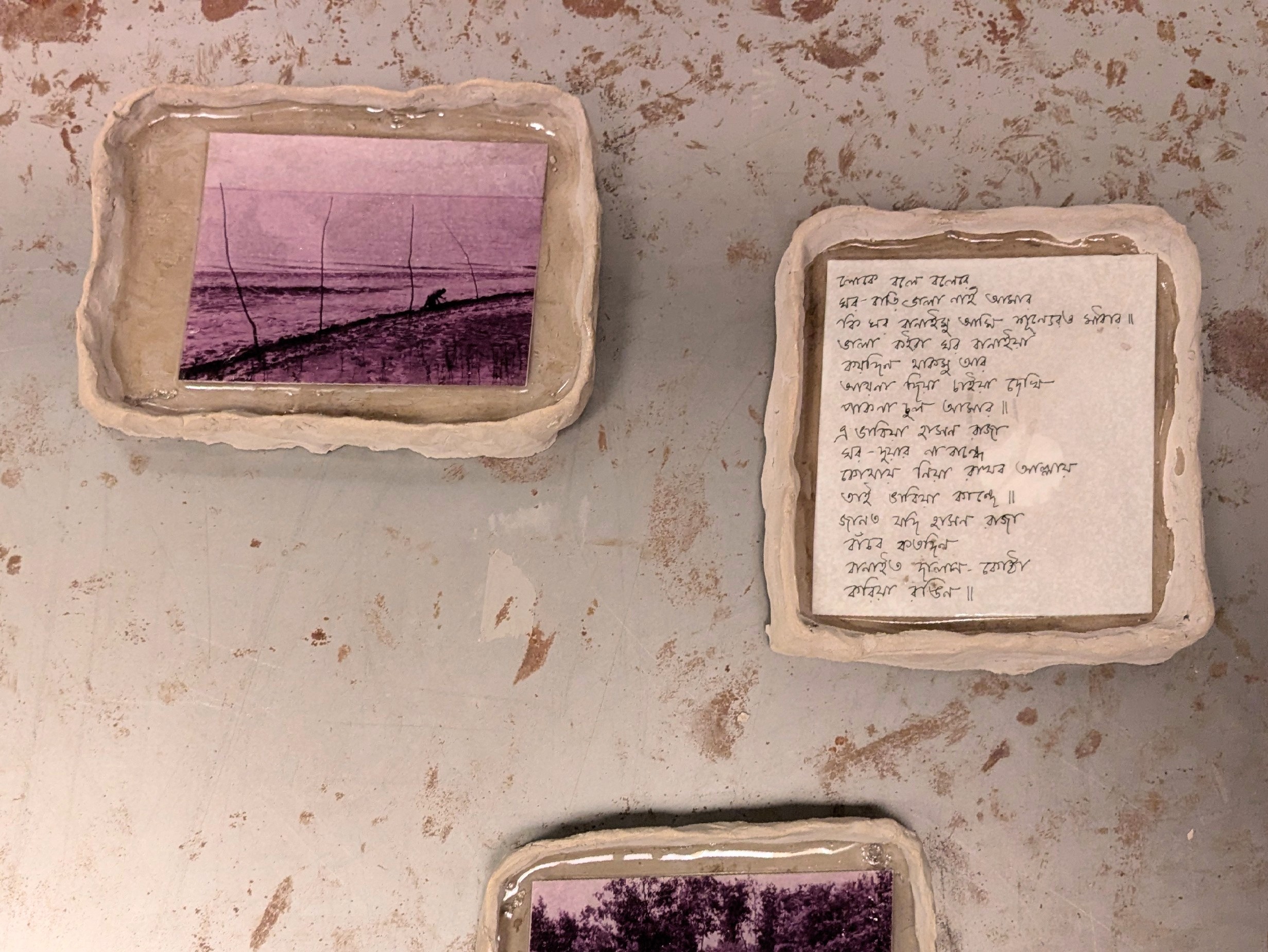

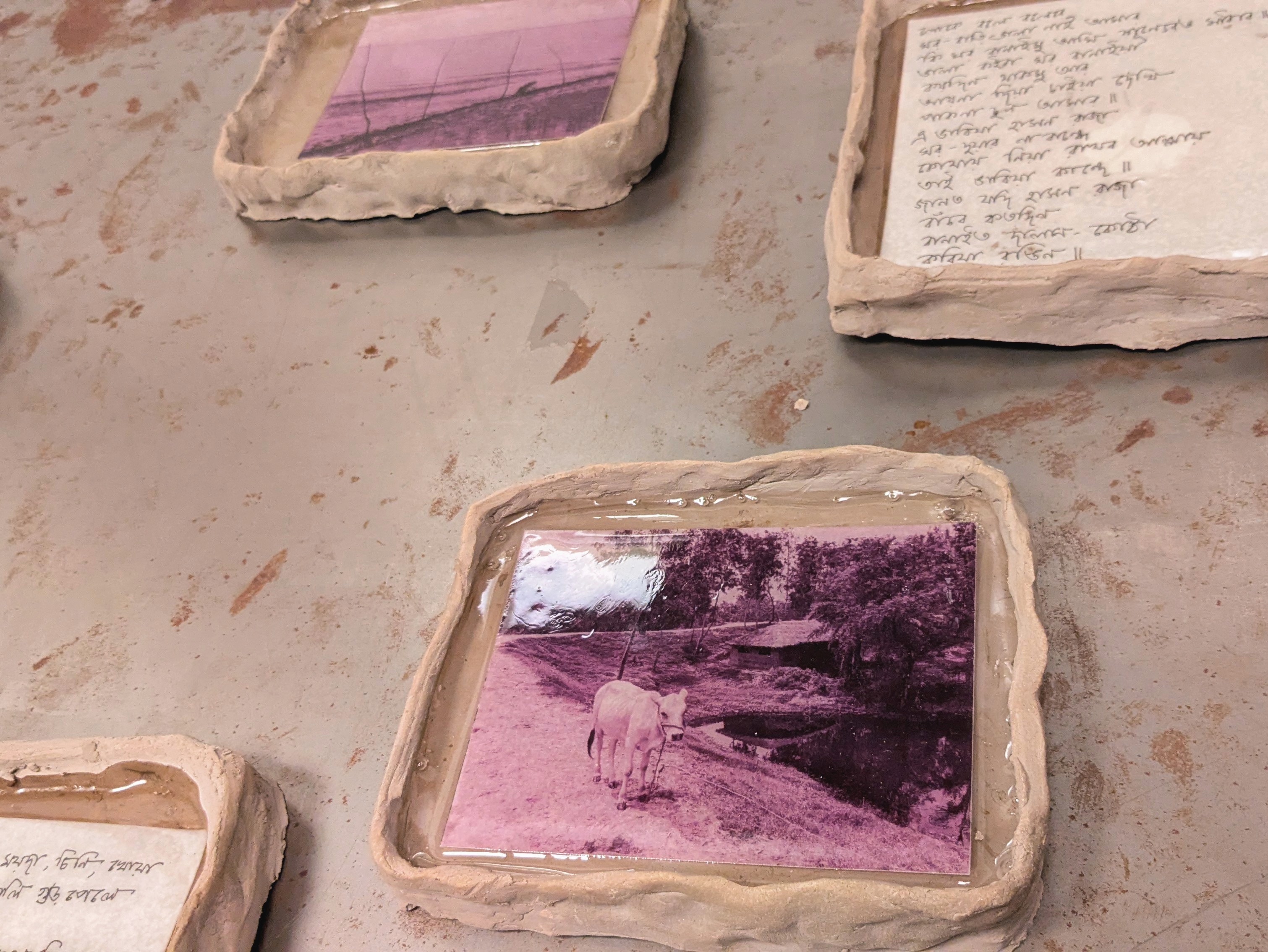

Clay, photography, text (Bengali), epoxy resin

2025

Inherited nostalgia is a phantom limb, an intangible relic of loss. As a fourth-generation migrant, I have no physical inheritance. Nostalgia refuses to be bound in lives lived out of suitcases, souvenir get lost in the constant displacement, the making and unmaking of homes. My inheritance rather takes the form of intangible culture passed down by my grandparents and parents: folk music, recipes, traditions, and languages of my ancestors.

Both sides of my parental lineage originate in present-day Bangladesh. A series of political upheavals on a timeline from 1947 till the 1980s displaced three generation in my family, as they moved first from present-day Bangladesh to West Bengal, and then to Mumbai. The first was the 1947 Partition of India. This was followed by the three Indo-Pakistan wars between 1948 to 1971 and the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. The mass inflow across the border caused a major refugee rehabilitation crisis in Bengal that was ill-managed by the Indian government. This was largely the cause of the massive economic crash of the 1980s in West Bengal, resulting in large-scale unemployment and migration. I spent my childhood and adolescence frequently moving places. The transgenerational trauma of the wars, displacement, economic loss and cultural alienation has been passed down to me from my parents and my grandparents. My cultural ties to Sylhet in Bangladesh, the home of my grandparents, which I have never visited, remain prominent in the languages I speak, my musical palette, cuisines, traditions and rituals. Revisiting the India-Bangladesh border areas, retracing the crossings of the family has been an essential part of my search for my roots. This artwork is a consequence of this search.

Silenced narratives in history and children of war often are bereaved thus of proof of their journey. Erasure is the first step of minority oppression. What museums harbour are largely the visible narratives of power structures of this world, while stories like my family’s get lost in the river of time and trauma. This series attempts to create an alternative archaeology, one that preserves intangible inheritance of migration. The ten “relics” preserve images from my travels to the riverine landscapes of the India-Bangladesh border areas, a recipe from my grandaunt of the Sylheti delicacy pithé, lyrics from two Baul songs, an oral folk music tradition from the land of my ancestors dating back to the fifteenth century.

The photographs and texts are cast in resin in a frame of unbaked clay. The use of unbaked clay is a reference to sculpting tradition in Bengal shared by both sides of the border, where This is part of a spiritual tradition of cyclicity where the objects sculpted remain degradable, carry the possibility of returning to the river where they came from. It becomes a metaphor for the way my family’s physical ties to East Bengal (present-day Bangladesh) have dissolved with time. On the other hand, the resin, materially, is the exact opposite, non-degradable and “preserving” these objects, it shall survive the degradation of the clay with the time, a speculative process for archaeologists of the future.